Amelia Nelson and her partner Nick struggled for five months to find a place in Toronto after their previous landlord informed them he wanted to renovate and then move his niece into the apartment. They started looking for a one-bedroom apartment with a maximum budget of $2,000, split between them.

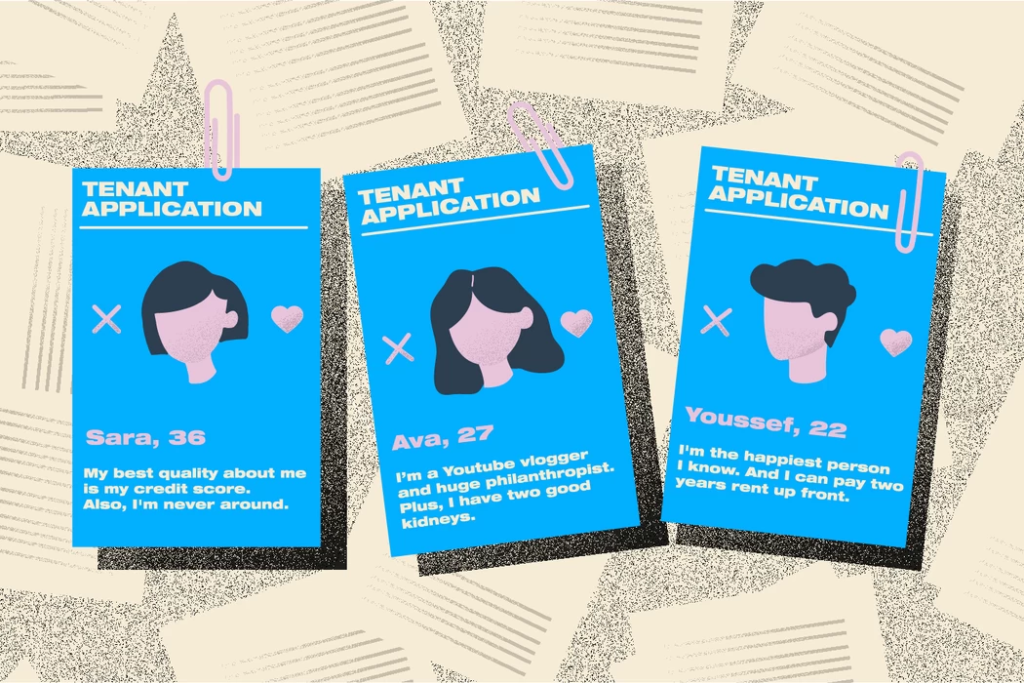

They enlisted six different real estate agents to help them, on top of scouring rental websites like Padmapper and Kijiji. They also created what Nelson describes as a dating profile of themselves as a couple.

The highlights included that they work in publishing and television, that neither of them smoke, that Nick — who doesn’t have permanent resident status and no credit in Canada — is from Australia, that Nelson has asthma and allergies which requires her to keep things clean, and that she is popular with neighbours.

“Nick and Amelia have been together for 3 and a half years and were just recently married,” the profile concludes. “They are a busy and ambitious pair, just starting out in their lives.”

But not everything in the profile is true, Nelson admits. For one, the couple is not married.

“[We also] doctored our employment letter to make [it look like we make] way more than we actually did. Even though we never searched places that were above our range, it seemed to matter.”

“It was a random agent that suggested we photoshop [Nick’s] credit score,” she told VICE News.

It’s just one example of what Toronto renters have been doing to ensure their application doesn’t get tossed in the trash pile, in what has become a ruthless competition to get a roof over your head in one of the biggest cities in the country.

The vacancy rate in Toronto is currently under 2 percent — the worst it’s been in 16 years — and the average monthly rent for a one-bedroom apartment has reached an astounding $2,200. According to a recent report from Urbanation, the average rent for a condo jumped 7.6 percent in the third quarter from a year ago to an all-time high of $2,385.

Meanwhile, Toronto Community Housing, the city’s subsidized housing agency, has been using a lottery system to select tenants for its buildings — recently, 75 in one and 59 in another — from a pool of thousands of applicants. The situation has become so dire that the Toronto Region Board of Trade says it’s impacting Toronto’s businesses, since a lack of places to live is affecting the city’s ability to retain talent.

“Current market conditions point to the fact that renters have little choice when it comes to finding a place to live,” said Toronto Real Estate Board President Garry Bhaura in a July report. “Governments need to look at ways to increase the supply of rental accommodation, both in terms of purpose-built rental properties and individual investor-held units. This would go a long way to easing the pace of rent growth in the GTA.”

The crisis, which has compelled some communities to mobilize against oppressive rent increases and eviction tactics, became a key issue in the recent municipal election. Mayor John Tory promised to keep property taxes low and build 40,000 affordable rentals in the next 12 years, while runner up Jennifer Keesmatt had pledged to build 100,000 units on city land in the next 10 years, 10,000 of which would have been “rent-to-own” homes.

The lack of rental housing stock means that if you haven’t apartment hunted in Toronto in the last several years, you’re in for a nasty surprise. The competition is fierce. Advertisements for roommates attract dozens of comments within minutes, often prompting the poster, who is overwhelmed by the number of inquiries, to stop scheduling viewings. If you do manage to get a viewing, you’ll likely bump into other applicants who have their first and last month’s deposit, an employment letter, and a credit check to hand over to the landlord on the spot. As a result, many apartment hunters find other ways to stand out from the crowd — lying in applications is common, as are bidding wars, with applicants offering to pay bigger deposits and sign onto longer leases. On Bunz Home Zone, apartment hunters frequently post photos of themselves, their partners, and their pets, accompanied by detailed written profiles.

“Now when you go to places, there can be lineups around the clock and viewings of 50 people, and so you have people, especially those who have been looking for a while, who are desperate, trying to find any way to get a place,” said Geordie Dent, executive director of the Federation of Metro Tenants Association. “So they’re outbidding folks, building personal profiles into their application, handing over personal information, just in case the landlord wants it, they’re promising not to have pets. These are things no tenant should have to do in Ontario, but they’re doing them anyway just to get a leg up.”

Justin Zychowicz searched online for weeks before moving from Calgary to Toronto, writing tens of lengthy, detailed messages about himself and his living habits to prospective landlords and roommates. The 24-year-old communications’ professional’s budget is around $1,000 a month for a bedroom in a shared apartment. He’s been living at an Airbnb for a month now, and still hasn’t found a place. He’s barely even been able to attend any viewings.

“I knew it was bad but I didn’t realize how bad it was,” Zychnowicz told VICE News.

“Every time I reach out to someone, even within five minutes of a post going up, most of these people have already received 40 to 50 comments or messages,” he said. “I’ve resorted to making video applications just to set myself apart from all the messages they receive, but it hasn’t really worked.”

It’s why real estate lawyers say that even when they’re helping clients with problematic landlords, they have been reluctant to advise them to move out of their apartments in search of a new one — because it would mean having to enter the unforgiving fray.

“If you go to a store and they don’t treat you right, then fine, you just go to a different store the next time,” said Dan McIntyre, a tenant advocate and paralegal in Toronto. “It’s not the same with rental because they keep raising the rates. Because of low vacancy rates, tenants are basically captive in their own apartment buildings.”

“We’re seeing more and more landlords claiming their son or daughter needs a place to live, so you gotta go,” said McIntyre. “We’re throwing more people to the wolves and more people are coming into Toronto without an adequate supply of rental housing, and the ridiculous prices that Toronto landlords are charging, which by the way they don’t need.”

It’s also enabled landlords in Toronto to make brazenly illegal requests of applicants in order to find the “perfect tenant” — and desperate applicants are often more than willing to comply.

Geordie Dent, executive director of the Federation of Metro Tenants Association, said the organization’s emails and phone lines are flooded with complaints.

In one case, a new immigrant was asked to pay a deposit of $36,000 in order to rent an apartment in Scarborough — three years’ rent. Asking for large deposits of up to six months’ rent, beyond first and last month’s rent, is becoming more and more common, and the targets tend to be new Canadians, said Dent.

Last year, one landlord demanded that applicants fill out an “honest renter” survey, which asked 100 questions, including whether or not they’re interested in other people’s problems, if they’ve ever done anything they’re ashamed of, and if they are normally sad — a question that Dent pointed could be considered discriminatory if the aim is to weed out applicants with mental illness and mood disorders.

William Blake, a senior member of the Ontario Landlords’ Association, says the challenges apartment hunters are facing will likely get even worse.

Landlords blame the competition on limited supply and rules that make it difficult to evict a bad tenant. He blames the competition not only on the limited supply of rental properties, but also on rules that make it difficult for landlords to evict a bad tenant. It can take so long to get an eviction hearing at the Landlord Tenant Board that landlords can be stuck in situations where the tenant isn’t paying rent, for example, for months at a time, said Blake, who has properties in multiple provinces and has been a landlord for over 20 years.

Rules that mostly work to protect tenants, as well as the inability to legally charge a damage deposit in Ontario, have made prospective landlords afraid of investing and more cautious about who they rent to, Blake added.

“For the big landlords, that’s ok, they have hundreds of units and economies of scale,” he said. “But for smaller landlords, going without rent for six or seven months can really bankrupt them.”

Blake does tenant screening the traditional way: a credit check, a letter of employment, previous landlord references, and an in-person meeting, and says the OLA always encourages its members to do the same. But it’s become common, he said, for companies that claim to do tenant screenings more effectively, advertising services like eviction risk scores and pet damage risk scores, to take advantage of new landlords, who are “looking for a magic wand.”

He knows they are crossing the line. “One of the companies asked, ‘if you are walking in a park and you see a piece of trash, will you pick it up and put it in the trash bin?’ And the justification was that the question was supposed to show whether or not the tenant will keep the property clean. How ridiculous is that?”

Dent and McIntyre both said they’d heard from women who have been propositioned to pay for rent with sexual favours, although neither was willing to go into specific cases.

In a list of anonymized complaints sent to VICE News by MTA, rental applicants say they’ve been asked everything from where they’re “originally from” to the genders of their children to whether or not they’ve ever had an affair.

“We have concerns about landlords wanting blue eyed, blonde-haired Harvard graduates over the general riff raff, so they’re able to pick and choose,” McIntyre told VICE News. “So that puts a lot of people in a hard place.”

Ultimately, Blake said, the problem comes down to a lack of supply.

“The supply is dwindling, the population is growing, and if the government doesn’t act, it’s just going to get tougher and tougher to find the rental homes,” he said. “We need more supply. We need the government to help landlords invest.”

All Nelson and her partner wanted was a clean non-smoking apartment within their budget, closer to their downtown jobs than her mother’s Scarborough home. Eventually they found one — for $1,800 including hydro in Liberty Village, thanks to a landlord who said he “liked helping young folks get their start.”

But the couple has had to sacrifice a significant amount of space and privacy. Nelson compares the living room and kitchen area to the size of her office receptionist’s desk.

“There’s a few places in the building you can go to if we need space from one another or something,” she said, adding that she’s watched a lot of videos about how to decorate a dorm room to get ideas for the small space. “And it’s clean and the landlord doesn’t live there, which is an upgrade from our last place.”